In the 1940s, the town of Shelburne, N.S., became home to a new garbage dump. Residential, industrial and medical waste from throughout eastern Shelburne County was burned at the dump over the decades, leaving nearby residents concerned about health issues.

The dump was situated uphill from the African Nova Scotian South End community, whose roots date back to the settlement of Black Loyalists who were evacuated from the United States after the Revolutionary War of 1776. Those near the dump worked, played and lived amid constant smells and smoke from burning garbage. The dump operated for 75 years, closing in 2016.

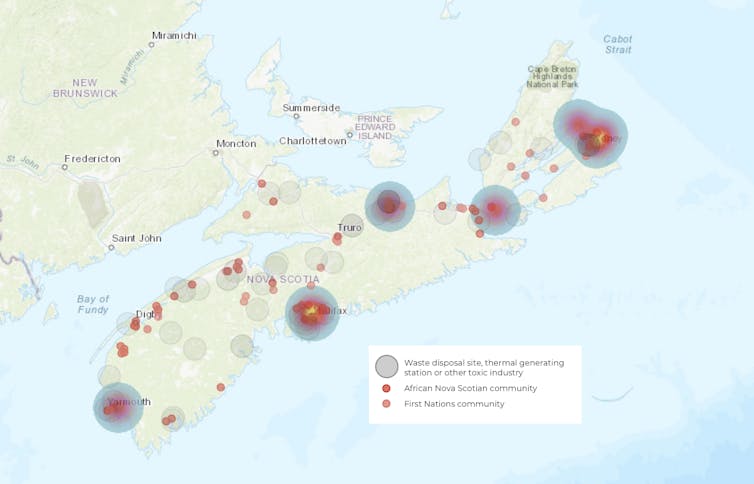

The placement of this dump was an act of what we now refer to as environmental racism — the disproportionate siting of polluting industries and other environmentally hazardous projects in Indigenous, Black and other marginalized communities.

Questions about the high rates of cancer — and deaths — among members of Shelburne’s African Nova Scotian community, compared to their white neighbours on the other side of town or even within the South End, have long simmered. We, along with our colleagues, are embarking on a major research project to determine whether the legacy of the dump may be even more sinister than people knew at the time.

Community-based research on environmental racism

Much of the motivation for the study comes from the work of local activist Louise Delisle, who has gone door-to-door in her community to catalogue cases of cancer, both recent and historical.

Previous and ongoing research and advocacy conducted through the Environmental Noxiousness, Racial Inequities & Community Health Project (the ENRICH Project), data in the book There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous & Black Communities and experiences of environmental racism shared by Nova Scotian community members in the Netflix documentary of the same name, confirm the necessity for such an investigation.

(ENRICH Project)

The data collected by the ENRICH Project over the years indicate that environmentally dangerous projects like dumps, landfills and pulp and paper mills are more likely to be sited in African Nova Scotian and Mi’kmaw communities, and that these communities suffer from high rates of cancer and respiratory illness.

Momentum to address environmental racism is also growing. A federal private member’s bill introduced by Nova Scotia MP Lenore Zann, the National Strategy to Redress Environmental Racism, passed second reading on March 24, 2021.

Read more:

Bill C-230 marks an important first step in addressing environmental racism in Canada

Bill C-230 returned to the federal Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development on June 21 for amendments, where it was approved a few days later. It will move to third reading in the fall of 2021, and then to the Senate, after which it may become Canada’s first legislation to address environmental racism.

Many factors influence cancer

As many factors can influence the incidence of cancer within a population, we’ll oversee a team spanning several research disciplines, with McMaster University serving as the hub and significant representation from Dalhousie University, co-ordinated by cancer biologist Paola Marignani.

Environmental chemical exposures, such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), can interact with biological and genetic factors, as well as social determinants of health, such as access to health care, race, gender and income, and lifestyle factors, such as diet, physical activity and smoking.

Our team will probe the contents of the dump to identify harmful materials such as heavy metals, volatile organic compounds and fine particulate matter, and we will examine genetic and epigenetic changes to the genomes of Shelburne residents that may explain cancer susceptibility.

We will also examine the extent to which race, gender, income and other social determinants of health contribute to cancer and premature death. The role of diet, exercise, smoking and other lifestyle factors in cancer incidence in Shelburne will also be studied given that existing studies indicate that these factors can increase our likelihood of getting cancer.

Cancer in Black communities

The study is multidisciplinary and complex. Yet we are confident it will help clarify the complex interactions between the social determinants of health, lifestyle factors, genetics and generational impact of chronic toxin exposure. It will also shed light on what is driving high cancer rates in South End Shelburne.

Our study will not just have value for the small community of Shelburne but will provide a template for further studies on the relationship between environmental racism and chronic diseases. For example, the African Nova Scotian community in Lincolnville, N.S., Indigenous communities such as Wet’suwet’en First Nation in northern B.C., and Aamjiwnaang First Nation near Sarnia, Ont., as well as African Americans living near Cancer Alley in Louisiana, who all live close to landfills, pipelines and petrochemical facilities, could all benefit from a similar multidisciplinary approach.

This study, and others like it, will bring us one step closer to addressing the wider problem of systemic racism in Canada.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.