Kyla Tienhaara, Queen’s University, Ontario

Kyla Tienhaara, Queen’s University, Ontario

The chickens have come home to roost for Alberta Premier Jason Kenney. Kenney bet around $1.5 billion of public money on a very risky prospect — the highly controversial Keystone XL pipeline.

U.S. President Joe Biden, to the surprise of no one but Kenney, followed through on an election promise and cancelled a key permit for the pipeline on the first day of his administration. Now the premier is scrambling for a way to recoup some of Alberta’s losses, and he sees a trade agreement as offering some hope.

The former North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) contained a chapter on investment that allowed foreign investors to sue governments in international arbitration. The owner of Keystone XL — TC Energy (previously TransCanada) — used NAFTA to launch a US$15 billion lawsuit in 2016 after President Barack Obama cancelled the project.

At the time, some legal experts thought the company had a reasonable chance of winning. We will never know, because the case was dropped when President Donald Trump indicated he was willing to let the project proceed.

(AP Photo/Evan Vucci)

This time may be different if TC Energy chooses to proceed with a claim. NAFTA has been replaced by a new agreement — the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Unlike NAFTA, USMCA does not permit Canadian investors to sue the U.S. government (or American investors to sue the Canadian government).

Legacy claims for investments that had occurred prior to the USMCA coming into force are permitted until 2023. But TC Energy’s claim may now be weaker because the permit issued by the Trump administration explicitly stated that it could be rescinded, essentially at the president’s whim.

Nevertheless, many investors have proceeded with claims on the basis of much weaker cases. Investors bet on positive outcomes in arbitration, as much as they bet on governments not taking action to halt catastrophic climate change. This is because the anticipated rewards, in both instances, are high.

Risky business

One example of an incredibly dubious investor claim is the one launched by Westmoreland Mining Holdings against Canada in 2018. Ironically, this case concerns action that the previous Alberta government took to address climate change.

Alberta’s 2015 Climate Leadership Plan included a provincial phaseout of coal power, which left Westmoreland — an American coal mining firm — without a future market for its coal. The company is arguing that Alberta’s failure to provide Westmoreland with “transition payments,” like those that power companies received, is a breach of NAFTA.

Read more:

The fossil fuel era is coming to an end, but the lawsuits are just beginning

The case is ongoing and outcomes of arbitration are very difficult to predict. But it demonstrates a concerning trend, as do other cases that have emerged in Europe.

Fossil fuel companies have been well aware of the damage their industry causes for decades, yet they have exerted substantial efforts to try to slow climate action. They have taken bets on risky investments in the hopes that governments would continue to dither as the planet burns. Now that climate action is starting to ramp up, they want to be “compensated” for their losses.

(AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

A global problem

Climate activists may be tempted to dismiss the threat that investment treaties pose to action on climate change. After all, the Canadian and U.S. governments have the resources to rigorously defend themselves in arbitration and they often win. Indeed, the U.S. has never lost a case. Furthermore, governments already subsidize the industry to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars per year, so is a few more billion in “compensation” really going to make much of a difference?

The problem is that climate change is a global issue and so too is the coverage of investment treaties. Many of the fossil fuel reserves that need to stay in the ground and assets that need to be stranded in order for us to remain below 1.5C of warming are in the Global South.

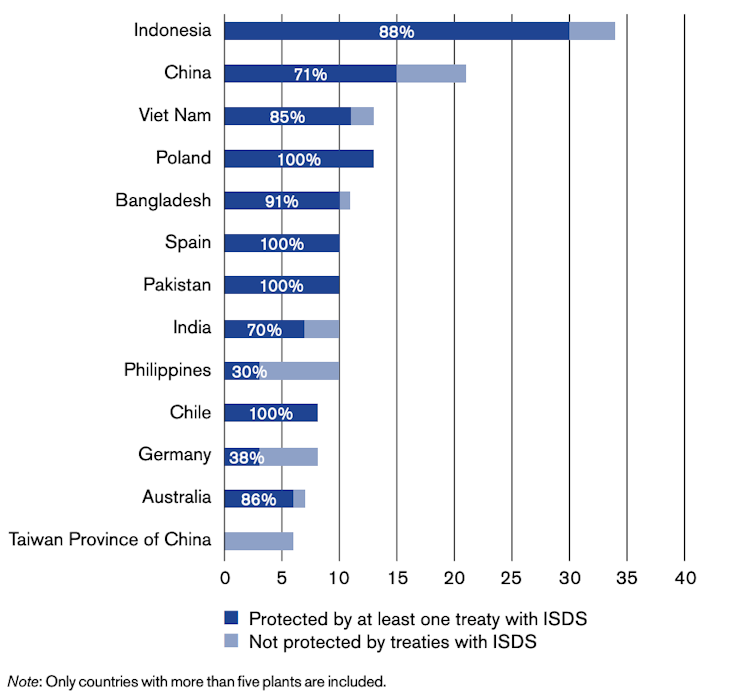

(Kyla Tienhaara and Lorenzo Cotula), Author provided

For example, a large number of planned and newly operating coal-fired power plants are in countries like Indonesia and Vietnam. A recent study found that many of these plants are protected by investment treaties. These countries have fewer resources for fighting claims and a much poorer record of success in arbitration.

A real concern is that even the threat of a big investor claim could be enough to dissuade one of these governments from taking action to phase out coal.

A global solution

We need climate action to happen everywhere, not just in the countries where governments can afford to fight legal challenges. This is one of the reasons why many are calling for radical reform or complete abolition of international investment treaties.

In Europe, campaigners are making headway on efforts to remove protection for fossil fuel investments from the Energy Charter Treaty. Countries like South Africa are pushing for investment treaties to be aligned with the Paris Agreement and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. Researchers have also suggested that the problems with investment treaties could be addressed with a Global Green New Deal.

In the meantime, the Canadian public should make it clear to TC Energy and Jason Kenney that they should drop any plans to pursue a legal challenge, and own up to the fact that they alone are responsible for their own poor investment decisions.![]()

Kyla Tienhaara, Canada Research Chair in Economy and Environment, Queen’s University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.